🔥Building an Enterprise Slack Bot with Agentic AI: A Complete AWS Architecture Guide🔥

aka, find outages in PagerDuty, identify changes in GitHub, find tickets in Jira, tie em all together

This blog series focuses on presenting complex DevOps projects as simple and approachable via plain language and lots of pictures. You can do it!

These articles are supported by readers, please consider subscribing to support me writing more of these articles <3 :)

Hey all!

Today we’re going to explore something pretty exciting in the world of enterprise AI applications. I recently got my hands on an evolution of the Vera genAI solution that I’ve covered extensively before - and this new version represents a significant architectural leap forward.

If you’ve been following my previous posts about Vera, you’ll remember it was built with Python directly without many external libraries, focusing on raw AWS Bedrock integration. This new implementation takes that foundation and transforms it into a proper agentic AI system using the Strands framework. Instead of just being a conversational AI, it can now take actions and use tools across your entire enterprise toolchain.

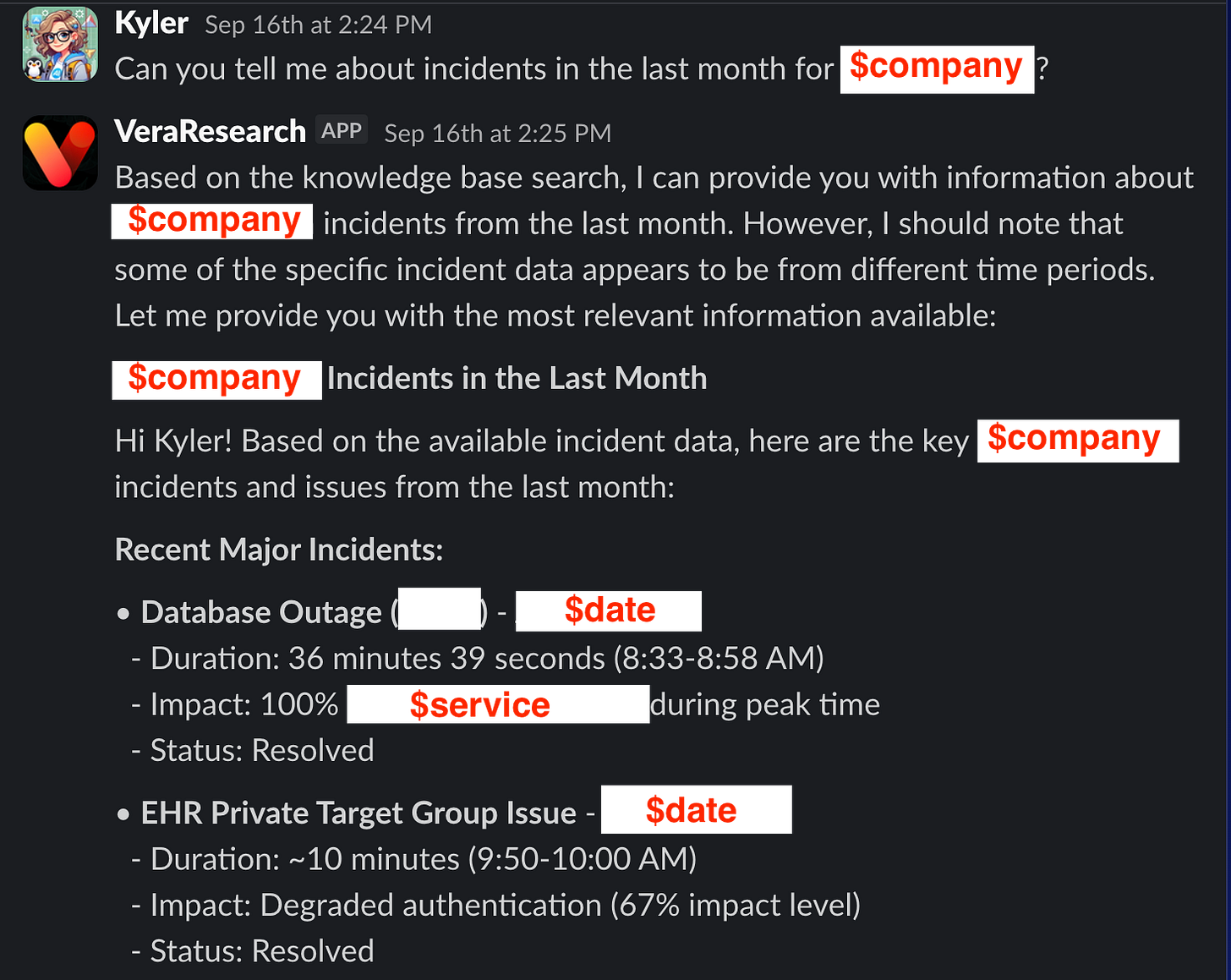

What makes this implementation particularly interesting is how it solves those everyday enterprise pain points we all know too well. You know that juggling act between Slack, PagerDuty, GitHub, and Jira just to get context on a single issue? This bot brings all those systems together in one conversational interface, powered by AWS Bedrock with Claude Sonnet 4 as the backend.

Here’s where the agentic capabilities really shine. The bot uses Model Context Protocol (MCP) to actually connect to your existing platforms. When someone asks “what incidents are assigned to me?” it goes and queries PagerDuty directly through AWS Bedrock’s processing. When they want to know about pull request status, it hits the GitHub API. The AI becomes a conversational interface to your entire toolchain, all orchestrated through AWS Bedrock’s model capabilities.

The system includes AWS Bedrock Guardrails for content filtering and even supports retrieval-augmented generation through Bedrock Knowledge Bases. It’s engineered for enterprise use with proper secret management, brand voice guidelines, and all the infrastructure automation you’d expect in a production environment.

In this article, we’ll walk through the complete architecture, examine how the Strands agentic framework transforms the original Vera approach, and look at how AWS Bedrock powers the multi-service integrations. Whether you’re thinking about building your own AI assistant or just curious about modern agentic architectures, this implementation has some great lessons to offer.

Let’s jump in and see how this all fits together!

If you want to skip the write-up and just read the code, you can find that here:

Containerizing the Worker Lambda: Why Docker Over Layers

When I started building this enhanced version of Vera, I quickly ran into a problem that anyone working with modern Python AI frameworks knows all too well: dependency hell.

The original Vera was relatively lightweight - just AWS SDK calls and some basic Slack integration. But this agentic version? We’re talking about the Strands framework, multiple MCP clients for different services, and a whole ecosystem of dependencies that each service brings along. The requirements.txt file exploded from a handful of packages to something that looked more like a small novel.

Lambda layers seemed like the obvious choice at first. After all, that’s what they’re designed for - sharing common dependencies across functions. But here’s where things got messy: we’re running on ARM64 for cost savings, and compiling some of these Python packages for ARM64 is a nightmare. Half the dependencies don’t have ARM64 wheels available, which means building from source. And building from source on ARM64? Good luck with that.

I spent way too much time trying to get a clean layer build working before I admitted defeat and switched to containers. Suddenly, all those dependency headaches disappeared. The AWS Lambda Python runtime base image handles the ARM64 compilation complexity, and I can use modern Python package managers like `uv` to handle the dependency resolution efficiently.

| # Use AWS Lambda Python runtime as base image for ARM64 | |

| FROM public.ecr.aws/lambda/python:3.12-arm64 | |

| # Ensure system packages needed to fetch/install uv are present (AL2023 uses dnf) | |

| RUN dnf -y install ca-certificates tar gzip && dnf clean all | |

| # Install uv (installs to /root/.local/bin by default) | |

| RUN curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh -s -- | |

| # Make uv readable and executable by all users | |

| RUN install -m 0755 /root/.local/bin/uv /usr/local/bin/uv \ | |

| && install -m 0755 /root/.local/bin/uvx /usr/local/bin/uvx | |

| # Put uv/uvx in PATH | |

| ENV PATH="/root/.local/bin:${PATH}" | |

| # Verify uv installation | |

| RUN uvx --version | |

| # Set environment variables | |

| ENV PYTHONPATH="${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}" | |

| # Copy requirements file | |

| COPY requirements.txt ${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}/ | |

| # Install Python dependencies | |

| RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt \ | |

| # Clean up to reduce image size | |

| && find /var/lang/lib/python3.12/site-packages -name "*.pyc" -delete \ | |

| && find /var/lang/lib/python3.12/site-packages -name "__pycache__" -exec rm -rf {} + 2>/dev/null || true \ | |

| && find /var/lang/lib/python3.12/site-packages -name "test*" -exec rm -rf {} + 2>/dev/null || true | |

| # Copy function code | |

| COPY src/*.py ${LAMBDA_TASK_ROOT}/ | |

| # Copy PagerDuty MCP server and pre-install dependencies | |

| COPY pagerduty-mcp-server /opt/pagerduty-mcp-server | |

| RUN cd /opt/pagerduty-mcp-server && \ | |

| uv sync --frozen && \ | |

| chmod -R a+rX /opt/pagerduty-mcp-server | |

| # Set the CMD to your handler | |

| CMD ["worker.lambda_handler"] |

The container approach gives us a few key advantages. First, we can pre-install and configure the MCP servers during the build process. Notice how we’re copying the PagerDuty MCP server into `/opt/` and running `uv sync` to install its dependencies. This happens at build time, not runtime.

Second, we get much more predictable dependency resolution. The `uv` package manager handles all the complex dependency trees and gives us reproducible builds. No more “it works on my machine” issues when deploying to Lambda.

Third, the container image becomes our deployment artifact. Terraform can build, tag, and push the image to ECR, then update the Lambda function to use the new image - all in one deployment cycle. No more managing separate layer deployments or worrying about version mismatches.

The performance impact has been minimal. Cold starts are slightly longer due to the larger image size, but the warm execution performance is actually better because all dependencies are pre-resolved and ready to go. For a Slack bot that processes messages intermittently, this trade-off makes perfect sense.

Code Organization: Breaking Up the Monolith

One thing I learned from the original Vera implementation was that shoving everything into a single Python file becomes a maintenance nightmare pretty quickly. The first version worked fine when it was just basic AWS Bedrock calls and Slack responses, but as soon as I started adding MCP integrations and agentic capabilities, that single file ballooned to over 800 lines.

This time around, I split things up from the start. The worker Lambda is now organized into focused modules, each handling a specific aspect of the bot’s functionality:

worker.py - Main Lambda handler and Slack app registration

worker_inputs.py - Configuration, constants, and system prompts

worker_agent.py - Strands agent setup and execution

worker_aws.py - AWS service integrations (Bedrock, Secrets Manager)

worker_slack.py - Slack-specific utilities and response formatting

worker_conversation.py - Message processing and conversation flow

worker_lambda.py - Lambda-specific utilities and event handling

worker_mcp_*.py - Individual MCP client implementations

| # Global imports | |

| import os | |

| import json | |

| # Slack app imports | |

| from slack_bolt.adapter.aws_lambda import SlackRequestHandler | |

| # Import all constants and configuration | |

| from worker_inputs import * | |

| ### | |

| # Local imports | |

| ### | |

| from worker_slack import update_slack_response, register_slack_app | |

| from worker_aws import ( | |

| get_secret_with_client, | |

| create_bedrock_client, | |

| ai_request, | |

| enrich_guardrail_block, | |

| ) | |

| from worker_agent import execute_agent | |

| from worker_conversation import build_conversation_content, handle_message_event | |

| from worker_lambda import isolate_event_body, generate_response |

The import structure shows how clean this separation becomes. Each module has a single responsibility, which makes testing and debugging so much easier. When something goes wrong with PagerDuty integration, I know exactly where to look. When I need to adjust the system prompt or brand voice, it’s all in `worker_inputs.py`.

What’s particularly nice about this approach is how it handles the MCP integrations. Each service gets its own module (`worker_mcp_pagerduty.py`, `worker_mcp_github.py`, etc.) that encapsulates all the client setup, authentication, and tool registration logic. The main agent module just imports what it needs and doesn’t have to worry about the implementation details.

This modular structure also makes the container build more efficient. Docker can cache layers better when dependencies are clearly separated, and the overall codebase becomes much more approachable for anyone who needs to maintain or extend it later.

MCP Protocol Integrations: Connecting External Tools

Here’s where things get really interesting. The Model Context Protocol is what transforms this from just another chatbot into an actual agentic system that can take actions across your toolchain. Instead of the AI just talking about your GitHub issues or PagerDuty incidents, it can actually query them directly and give you real-time information.

The beauty of MCP is that it provides a standardized way for AI models to interact with external systems. Each service exposes its capabilities as “tools” that the AI can discover and use dynamically. When someone asks “what incidents are assigned to me?” the bot doesn’t just guess - it calls the PagerDuty API through the MCP interface and gets the actual data.

I filter all tools in their own file, so I can only return tools to the agent that can do READ behavior (non-modify). AIs are way too scary to give them write tools, IMO. You can say read-only = False if you want all the Write tools also.

PagerDuty Integration

The PagerDuty integration handles incident management and on-call scheduling. The MCP server runs as a pre-installed component in the container, which means zero cold-start overhead when the bot needs to query PagerDuty.

| def build_pagerduty_mcp_client(pagerduty_api_key, pagerduty_api_url): | |

| """Build PagerDuty MCP client with available tools""" | |

| # Build the PagerDuty MCP client | |

| pagerduty_mcp_client = MCPClient( | |

| server_path="/opt/pagerduty-mcp-server", | |

| server_args=[], | |

| server_env={ | |

| "PAGERDUTY_API_KEY": pagerduty_api_key, | |

| "PAGERDUTY_API_URL": pagerduty_api_url, | |

| }, | |

| ) | |

| # List available tools from the PagerDuty MCP server | |

| available_tools = pagerduty_mcp_client.list_tools() | |

| print(f"🟡 Available PagerDuty MCP tools: {[tool.name for tool in available_tools]}") | |

| # Convert MCP tools to Strands-compatible tools | |

| pagerduty_tools = [ | |

| pagerduty_mcp_client.create_tool(tool) for tool in available_tools | |

| ] | |

| return pagerduty_mcp_client, pagerduty_tools |

The setup is straightforward - we pass the API credentials through environment variables and let the MCP client discover what tools are available. The PagerDuty MCP server typically exposes tools for listing incidents, getting on-call schedules, and querying service status.

GitHub Integration

GitHub integration is particularly useful for development teams. The bot can pull pull request status, check repository information, and even search across codebases. I’ve implemented it with read-only access by default because, let’s be honest, you probably don’t want your Slack bot accidentally merging pull requests.

| def build_github_mcp_client(github_token, access_level="read_only"): | |

| """Build GitHub MCP client with specified access level""" | |

| # Set up environment for GitHub MCP | |

| github_env = { | |

| "GITHUB_TOKEN": github_token, | |

| } | |

| # Build the GitHub MCP client using streamable HTTP client | |

| github_mcp_client = MCPClient( | |

| server_factory=lambda: streamablehttp_client("http://localhost:8000/mcp"), | |

| server_env=github_env, | |

| ) | |

| # List available tools from GitHub MCP | |

| available_tools = github_mcp_client.list_tools() | |

| print(f"🟡 Available GitHub MCP tools: {[tool.name for tool in available_tools]}") | |

| # Filter tools based on access level | |

| if access_level == "read_only": | |

| # Only include read-only operations | |

| read_only_patterns = [ | |

| "get_", "list_", "search_", "download_", "read_", | |

| "mcp__github__get", "mcp__github__list", "mcp__github__search" | |

| ] | |

| filtered_tools = [ | |

| tool for tool in available_tools | |

| if any(pattern in tool.name for pattern in read_only_patterns) | |

| ] | |

| else: | |

| # Include all tools for full access | |

| filtered_tools = available_tools | |

| # Convert to Strands-compatible tools | |

| github_tools = [ | |

| github_mcp_client.create_tool(tool) for tool in filtered_tools | |

| ] | |

| print(f"🟢 Using {len(github_tools)} GitHub tools in {access_level} mode") | |

| return github_mcp_client, github_tools |

The filtering logic here is important. By restricting to read-only operations, we get all the query capabilities without the risk of destructive actions. The bot can tell you about issues, pull requests, and repository status, but it can’t modify anything.

Atlassian Integration

The Atlassian integration covers both Jira and Confluence, which makes it incredibly powerful for teams that live in the Atlassian ecosystem. The OAuth setup is a bit more complex than the other integrations, but once it’s configured, the bot becomes a conversational interface to your entire knowledge base.

| def build_atlassian_mcp_client(refresh_token, client_id, access_level="read_only"): | |

| """Build Atlassian MCP client with OAuth credentials""" | |

| # Set up environment for Atlassian MCP | |

| atlassian_env = { | |

| "ATLASSIAN_REFRESH_TOKEN": refresh_token, | |

| "ATLASSIAN_CLIENT_ID": client_id, | |

| } | |

| # Build the Atlassian MCP client | |

| atlassian_mcp_client = MCPClient( | |

| server_factory=lambda: streamablehttp_client("http://localhost:8001/mcp"), | |

| server_env=atlassian_env, | |

| ) | |

| # List available tools from Atlassian MCP | |

| available_tools = atlassian_mcp_client.list_tools() | |

| print(f"🟡 Available Atlassian MCP tools: {[tool.name for tool in available_tools]}") | |

| # Filter tools based on access level | |

| if access_level == "read_only": | |

| # Only include read/search operations for Jira and Confluence | |

| read_only_patterns = [ | |

| "get_", "list_", "search_", "read_", "fetch_", | |

| "jira_search", "confluence_search", "get_issue", "get_page" | |

| ] | |

| filtered_tools = [ | |

| tool for tool in available_tools | |

| if any(pattern in tool.name.lower() for pattern in read_only_patterns) | |

| ] | |

| else: | |

| # Include all tools for full access | |

| filtered_tools = available_tools | |

| # Convert to Strands-compatible tools | |

| atlassian_tools = [ | |

| atlassian_mcp_client.create_tool(tool) for tool in filtered_tools | |

| ] | |

| print(f"🟢 Using {len(atlassian_tools)} Atlassian tools in {access_level} mode") | |

| return atlassian_mcp_client, atlassian_tools |

What’s particularly clever about the Atlassian integration is how it handles both Jira tickets and Confluence documentation in a unified way. When someone asks about a project, the bot can pull information from both systems and present a complete picture.

The key insight with all these integrations is that they’re designed to fail gracefully. If a service is unavailable or credentials are missing, the bot continues to work - it just operates without those specific tools. This makes the system much more resilient in production environments.

Terraform Container Deployment: Building and Deploying Docker Images

One of the things I really appreciate about this architecture is how Terraform handles the entire container lifecycle. Unlike traditional Lambda deployments where you’re uploading zip files and hoping for the best, this approach treats the container image as the deployment artifact and manages everything from build to deployment in a single workflow.

The magic happens through a combination of ECR repository management and some clever null_resource provisioners that handle the Docker build and push operations. When you run `terraform apply`, it doesn’t just update your Lambda configuration - it actually builds a fresh container image, pushes it to ECR, and then updates the Lambda function to use that new image.

| # ECR Repository for container images | |

| resource "aws_ecr_repository" "worker_container" { | |

| name = "${var.bot_name}-worker" | |

| image_tag_mutability = "MUTABLE" | |

| image_scanning_configuration { | |

| scan_on_push = true | |

| } | |

| lifecycle_policy {} | |

| } | |

| # Build and push Docker image using null_resource | |

| resource "null_resource" "docker_build_push" { | |

| triggers = { | |

| # Rebuild when any source file changes | |

| source_hash = data.archive_file.lambda_source.output_md5 | |

| } | |

| provisioner "local-exec" { | |

| command = <<-EOF | |

| # Login to ECR | |

| aws ecr get-login-password --region ${data.aws_region.current.name} | docker login --username AWS --password-stdin ${aws_ecr_repository.worker_container.repository_url} | |

| # Build image for ARM64 | |

| docker build --platform linux/arm64 -t ${aws_ecr_repository.worker_container.repository_url}:latest . | |

| # Push image | |

| docker push ${aws_ecr_repository.worker_container.repository_url}:latest | |

| EOF | |

| working_dir = "${path.module}" | |

| } | |

| depends_on = [aws_ecr_repository.worker_container] | |

| } | |

| # Worker Lambda function using container image | |

| resource "aws_lambda_function" "worker" { | |

| function_name = "${var.bot_name}-Worker" | |

| role = aws_iam_role.lambda_execution_role.arn | |

| # Container configuration | |

| package_type = "Image" | |

| image_uri = "${aws_ecr_repository.worker_container.repository_url}:latest" | |

| ... |

The ECR repository includes lifecycle policies that automatically clean up old images, which is important because container images can get pretty large. We keep the latest 10 tagged images and automatically delete untagged images after a day. This prevents your ECR costs from spiraling out of control as you iterate on the deployment.

The Docker build process is particularly clever here. The null_resource uses a trigger based on the source file hash, so it only rebuilds the image when your code actually changes. This saves a ton of time during development when you’re just tweaking Terraform configurations without touching the application code.

What’s really nice about this approach is how it handles the ARM64 build process. The `--platform linux/arm64` flag ensures we’re building for the correct architecture, and since we’re building on the same platform where Terraform runs, we avoid all those cross-compilation headaches that made Lambda layers so problematic.

The Lambda function configuration shows how seamlessly containers integrate with the rest of AWS Lambda. You still get all the same configuration options - memory size, timeout, environment variables - but now your entire dependency tree is packaged as a single, immutable artifact. No more worrying about layer compatibility or missing dependencies.

Environment variables are passed through cleanly, including the MCP feature flags that control which integrations are enabled. This means you can deploy the same container image to different environments with different capabilities just by changing the Terraform variables.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

Building this enhanced version of Vera taught me quite a few things about modern agentic AI architectures, and honestly, some hard lessons about when to stick with what works versus when to embrace new approaches.

Container vs Layers: The Right Tool for the Job

The biggest lesson here was accepting that Lambda layers, while great for simple shared dependencies, just weren’t going to cut it for this complexity level. The original Vera worked fine with layers because it had a handful of lightweight dependencies. But once you’re dealing with the Strands framework, multiple MCP clients, and all their transitive dependencies, containers become the only sane choice.

The decision framework I’d use now: if your requirements.txt has more than 20 packages or includes any packages that need native compilation, just go straight to containers. The development experience is so much better, and the deployment reliability gains are worth the slightly larger cold start times.

Performance Considerations

Speaking of cold starts, they’re definitely longer with the container approach - usually 2-3 seconds instead of sub-second for the original Vera. But here’s the thing: for a Slack bot, this rarely matters. Most conversations happen in bursts, so the function stays warm. And when it does cold start, users are already expecting some delay for “AI thinking time.”

What surprised me was how much faster the warm execution became. All those dependencies are pre-resolved and ready to go, which makes the actual AI processing noticeably quicker. The MCP clients can establish connections faster, and there’s less Python import overhead.

Scaling Challenges and Solutions

The current architecture handles our team’s usage just fine, but I can see some potential bottlenecks as usage grows. Each Lambda invocation opens its own MCP client connections, which could become problematic if we’re hitting rate limits on external APIs.

The next evolution would probably involve connection pooling or even moving some of the MCP operations to separate services that can maintain persistent connections. But honestly, that’s a nice problem to have - it means people are actually using the bot.

Modular Architecture Payoffs

The decision to break everything into focused modules has paid dividends already. When GitHub changed their API authentication requirements, I only had to touch `worker_mcp_github.py`. When we wanted to adjust the system prompt for better Slack formatting, it was all in `worker_inputs.py`.

This modularity also makes testing much more manageable. You can unit test individual MCP integrations without spinning up the entire Lambda environment, which speeds up the development cycle considerably.

Future Enhancement Opportunities

There are several directions this could evolve. Adding more MCP integrations is the obvious one - imagine connecting to ServiceNow, Datadog, or your internal APIs. The framework makes this relatively straightforward now.

I’m also interested in exploring memory and context persistence. Right now, each conversation is stateless, but there’s real value in the bot remembering previous interactions or maintaining context across related conversations.

The Strands framework also supports more advanced agentic behaviors like multi-step planning and tool chaining. We’re barely scratching the surface of what’s possible when you give an AI system the ability to orchestrate multiple API calls to solve complex problems.

Summary

It’s been super fun to build out this new platform, and I’ve been able to re-use many of the pieces of the original genAI Vera, particularly the pieces that integrate with Slack.

The bot is quite a bit slower than genAI Vera, but can answer questions like this:

“Show me critical incidents for my team” - pulls live PagerDuty data

“Status of the auth PR?” - queries GitHub directly

“Find our API rate limiting docs” - searches Confluence with links

“What’s blocked this sprint?” - filtered Jira queries

And because of using MCP tools, the answers are less often hallucinated, and more often backed by information the tool fetches.

Instead of bouncing between Slack, PagerDuty, GitHub, and Jira for incident context, teams get comprehensive answers from one question. On-call engineers can query previous incidents, service status, and recent code changes without leaving their response channel.

Hopefully it can help you too. Good luck out there!

kyle